Picture perfect

Authors, playwrights, poets, actors, actresses, politicians and elder statesmen… as is evident in an exquisite new collection of his photographs and profiles – edited by his literary executor Hugo Vickers – Cecil Beaton brought his unique visual language to every portrait.

He invariably placed his subjects in particular context; a young Queen on her throne, an actor on stage, a fashion designer in their salon.

His positioning was deliberately contrived, but without parody, often spending hours, days even, ‘setting the scene’. Doors opened for him because he didn’t apply rose-tinted spectacles. Rather, he sought out his subjects’ fault lines and worked hard to eliminate them.

1. Contact sheet for Marilyn Monroe (1956) 2. Cecil Beaton, self-portrait (1936) 3. Elizabeth Taylor (1957)

1. Contact sheet for Marilyn Monroe (1956) 2. Cecil Beaton, self-portrait (1936) 3. Elizabeth Taylor (1957)Occasionally someone would come along who needed little help. According to Beaton, Grace Kelly was naturally ‘photogenic’. She had the requisite combination of small nose (protruding noses cast shadows), strong cheekbones, square jowls and ‘amusement’ puff s beneath her eyes.

Beaton’s own profi le reads like a blueprint for all the grand highlights of the 20th century. Born into upper-middle-class grandeur in Hampstead, London in 1904, he was too young for the First World War and arrived instead at Cambridge in 1922, leaving three years later without a degree – a testament not to his stupidity, but his utter devotion to all things social.

He acquired his first camera at the age of 11 and used his sisters as models, dressing them in theatrical outfi ts in decadent settings, a theme that occurred regularly throughout his work. His were the images of the ever-changing cast of Bright Young Things who fi lled the pages of Vogue for more than 25 years. But he was far from a hired gun.

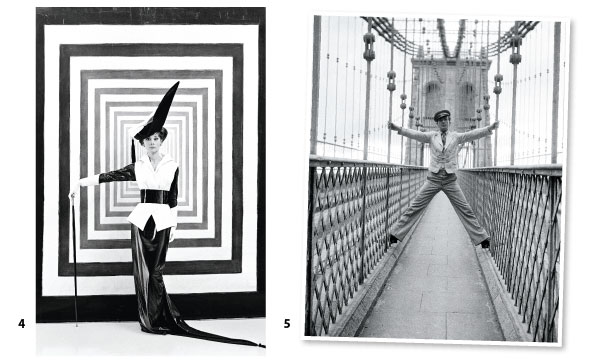

4. Audrey Hepburn on the set for My Fair Lady (1963) 5. Self portrait on Brooklyn Bridge (1929)

4. Audrey Hepburn on the set for My Fair Lady (1963) 5. Self portrait on Brooklyn Bridge (1929)In 1968, for instance, he was asked to photograph Elizabeth Taylor again (the two had worked together many times in the 1950s) but he deliberately requested an exorbitant fee of $5,000 and was delighted to be turned down. ‘She’s everything I dislike,’ he said.

He was also a perfectionist. Long before Photoshop, Beaton would spend hours editing and touching up the final results of shoots in order to achieve the very best effect. Shoots were invariably accompanied by extensive note-taking ‘pen portraits’, and each still in the book is accompanied by his comments on the day.

And so we learn that he and Marilyn Monroe met only once, in 1956, which largely involved him chasing her round his hotel suite for 45 minutes ‘snapping’ a series of portraits that have come to earn that overused label ‘iconic’. Marilyn flounced in an hour and a half late, yet the exacting Beaton was clearly smitten. ‘Her voice, of a loin-stroking affection, has the sensuality of silk or velvet,’ he wrote. ‘She romps, she squeals with delight, she leaps on the sofa… It is an artless, impromptu, high-spirited, infectiously gay performance. It will probably end in tears.’ He was right, of course.

6. Fred Astaire and his sister Adele (1930) 7. Marilyn Monroe (1956) 8. Nancy Mitford (1929)

6. Fred Astaire and his sister Adele (1930) 7. Marilyn Monroe (1956) 8. Nancy Mitford (1929)In 1937, he became official court photographer to the Royal Family, allowing him rare access to the soft underbelly of court life. ‘The Queen has a genius for making every man feel she needs his protection,’ his notes recall of a shoot in 1939 with the Queen Mother. ‘Princess Margaret is infinitely more photogenic [than Princess Elizabeth] and becomes increasingly so as the years bring her to maturity,’ he noted after a sitting with her youngest daughter in 1951.

Yet it was the young Princess Elizabeth with whom he developed a lifelong affinity. It was Beaton who was called upon to photograph her in full regalia, following her Coronation in 1953. Seated on her throne, the result is one of the most captivating images of a monarch ever produced.

Beaton’s notes from that day speak volumes about a young Royal with the weight of a new dawn placed on her shoulders: ‘The Queen looked very small under her robes and crown, her nose and hands rather pink – also her eyes somewhat tired. Yes, in reply to my question, the crown does get rather heavy. One couldn’t imagine she had been wearing it for nearly three hours.’

9. Julie Andrews (1959) 10. Three-year-old Blitz victim Eileen Dunne in a hospital bed (1940)

9. Julie Andrews (1959) 10. Three-year-old Blitz victim Eileen Dunne in a hospital bed (1940)Many might have thought that the Royal Family would have dropped him after his foolish introduction of some anti-Semitic words in a design for Vogue in 1938, but in fact it was the Queen Mother who offered him a lifeline when she suggested he do propaganda work for the war effort. He joined the Ministry of Information and produced some of the most arresting images of the era – his 1940 portrait of three-year-old Blitz victim Eileen Dunne in a hospital bed ending up on the front cover of Life magazine.

Cecil Beaton was surrounded by stars, but his real skill was knowing that luminosity could come from anywhere.

Cecil Beaton: Portraits & Profiles, by Cecil Beaton, edited by Hugo Vickers (Frances Lincoln, £30).