Where there’s a willow there’s a way

PH Coate & Son, which was founded in 1819 by Robert Coate and is still run by the family in Somerset today, is one of Britain’s last surviving willow growers. Nicola Coate now runs the business (which currently has 90 acres of coppice willow) with her husband, the basket and furniture maker Jonathan Coate. It is a mini industry: they grow the willow, harvest it and then use it to manufacture a range of goods.

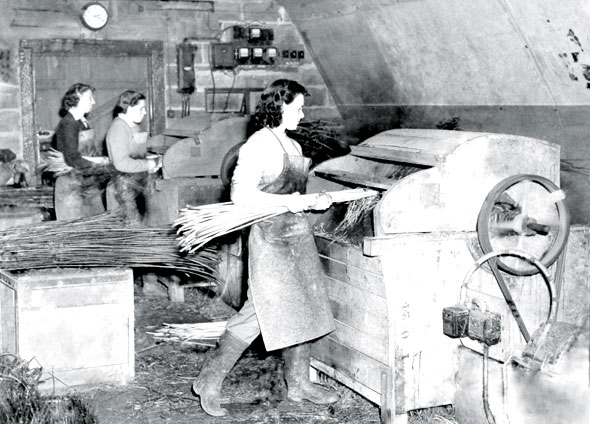

‘We get 17,000 plants per acre,’ Nicola tells me. ‘There aren’t many people who can make traditional furniture from willow, so Jonathan’s keeping that skill alive.’ There are five permanent weavers on site who can make a shopping basket in an hour and a half, and a coffin in 10 hours.

‘We have four men and one woman,’ says Nicola. ‘Traditionally, it’s always been men. To weave at speed, you need to have incredible strength in your hands and, naturally, men have that strength. A lot of women do it as a hobby, but to enable us to sell things at a sensible price, if it took them days and days we’d never be able to sell anything.’

The family firm also makes the hampers for Fortnum & Mason. Nicola tells me the charming tale of how their affiliation came to be. ‘This is only the third year that we’ve made for the company. A buyer came down and was looking in the storeroom with my husband. He is a big chap – 6ft 4in – and he grabbed a hamper and stood on it to find something on a higher shelf. The buyer looked at him and said, “My goodness, if you did that with one of ours you’d have gone straight through.” It wasn’t staged, it was just he needed to reach something.

‘We offer a good service, we make what they want, we do the stencilling [of Fortnum’s logo], and they are proud to buy British. And we’re proud to supply them.’

The company’s skills have even attracted Hollywood’s attention (they were also involved with the opening ceremony of the London Olympics), and they have made props for films such as this year’s Maleficent, Sweeney Todd, and War Horse. ‘There were a lot of shell baskets needed for War Horse – there were so many takes, they were constantly being blown up,’ says Nicola.

The company still has military links today – they make the internal frames for the bearskin hats worn by the Army’s Foot Guards regiments. One of the earliest is in their on-site museum, which is filled with extraordinary artefacts from the industry’s history.

‘War Horse was really interesting because it led us to a whole new story for our museum that we had never been aware of. We knew about medical panniers and pigeon baskets but we weren’t really aware of the shell baskets.’

The museum is home to one of the largest collections of willow artefacts in the UK.

‘We have around 200 items. It’s a unique collection – I can’t think that many other people would want to collect them,’ she laughs, ‘but it’s so poignant and relevant to us. We collect different things that have been made in the area, but we also have items from around the UK. We want to have as many different baskets that represent all the different techniques.’

Producing items for Hollywood may lead people to believe that the family has been sailing along without a worry. Things haven’t always been easy, and the Coate family have had to adapt to survive. But how? ‘By the skin of our teeth,’ Nicola exclaims. ‘There were some very difficult times. The high point was during the war, but with plastics coming in soon afterwards, the industry declined rapidly. The 1960s and 1970s were difficult as plastics were taking over from everything. Now it’s competition from cheap, imported baskets.

‘Shoppers buy a washing basket for £10 and don’t think anything of it, but that’s still probably been handmade and transported; people don’t think about what the person who made it was paid. Our basketmakers are paid as skilled craftspeople so our products are a little more expensive than others on the market. But they last an awful lot longer. It’s part of the whole wider landscape of this part of the world. We’re keeping a heritage craft alive.’

Jonathan’s grandfather also had to adapt to changing times. ‘A large part of what helped us to survive was artists’ charcoal,’ Nicola explains. ‘My husband’s grandfather experimented with making artists’ charcoal and soon perfected a technique using willow, which was consistently good. Once they started marketing it that filled a niche for us. Now we use it for half of our crop. We export it all over the world… it makes very soft charcoal which is why it’s so popular.

‘We also make a lot of coffins these days, another growing part of the business. You just have to keep moving.’ But despite competition, Mother Nature seems to be the biggest threat. ‘We harvest in midwinter once the leaves have fallen,’ Nicola says, ‘but with global warming, it’s getting later and later – we tend to do it around November time now. It’s pretty warm here, and last year we didn’t even have a frost. The planting is in the late spring, but the main thing that aff ects the production is flooding. That was like nothing we could ever have imagined.

‘We started harvesting in November, the floods came in December and didn’t go until late March. That really interfered with the planting. We had to do three months’ work in three weeks. It was totally submerged in places, two metres deep.’

You have to admire Nicola’s spirit – when I ask her if she has any plans on how they might cope with flooding in the future, she replies: ‘Turn our harvesting machine into a submarine and give our guys scuba lessons.’

Despite the fact she is refreshingly upbeat about a worrying situation, Nicola does tell me they have thought about contingency plans. ‘Obviously, we’ve got an idea of how things could change. We will make plans, but to create a willow bed takes three years so you can’t just think, “Okay, we’ll plant over there,” like you can with wheat and arable crops. It’s much more long-term than that. Yes, you might be able to do that in five years’ time, but the business has to survive while we make adjustments. We just hope the dredging and other schemes that were put into place do work. We want a nice cold winter. That would be great.’

PH Coate & Son, Meare Green Court, Stoke St Gregory, Taunton, Somerset: 01823-490249, www.englishwillowbaskets.co.uk