The prince & the pottery

Three years ago, Middleport Pottery, which was opened in 1888 by ceramics manufacturer Burgess & Leigh and is famed for its blue-andwhite Burleigh ware, was on its last legs. Like so many other domestic potteries, it was in economic peril. The end was nigh; the wrecking ball loomed.

BACK FROM THE BRINK

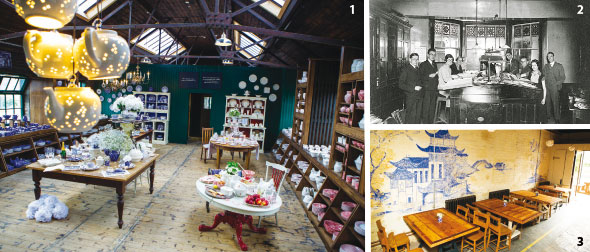

But HRH The Prince of Wales’s charity, The Prince’s Regeneration Trust, has changed that. In 2011, it began a £9m regeneration project of the Grade II-listed buildings, an ambitious scheme only just completed, which has ensured that Middleport, in Burslem, Stoke-on-Trent, remains our last working Victorian pottery. 1. Burleigh ware is beautifully displayed in the factory shop 2. Staff in the general office of Middleport Pottery pose in the 1930s 3. An original Burleigh design decorates a wall in the cafe

1. Burleigh ware is beautifully displayed in the factory shop 2. Staff in the general office of Middleport Pottery pose in the 1930s 3. An original Burleigh design decorates a wall in the cafe It is certainly a very special place. As Prince Charles began a tour through the dusty factory buildings, during which he met ‘glost selector’ Carole Mantle, the pottery’s longest-serving current employee, I had the opportunity to explore, too. And it is filled with treasures, including a magical collection of moulds.

There are more than 19,000 moulds – including an extraordinary one of a bird’s two legs (they haven’t found the bird they belong to yet) – in this atmospheric archive and many are still being catalogued. It is one of the biggest collections of its kind in the world and includes everything from historic bedpans to exquisitely crafted models of Shakespearean characters.

But Middleport is far more than just a nostalgic throwback to our industrial past. It is also about people – and maintaining skills that are in danger of being lost forever.

4. Red Felicity and Red Calico patterns 5. Teapots await decoration 6. Tissue rolls off a machine, then is cut ready for application to biscuit-ware pots

4. Red Felicity and Red Calico patterns 5. Teapots await decoration 6. Tissue rolls off a machine, then is cut ready for application to biscuit-ware pots‘Ceramics are, in many ways, Britain’s gift to the world,’ said Steven Moore, ambassador for the Trust and an expert on the Antiques Roadshow. ‘Josiah Wedgwood, here in Stoke, revolutionised the production of ceramics using the processes of the Industrial Revolution. All the techniques of all the china that everybody has at home were used here for centuries, but this is the last place in the whole world that still transfers prints by hand.

‘The prints come off a copper roller and are then applied by hand. It looks like a very simple operation but it takes seven years to learn that skill. So, here, it’s not just the buildings themselves and the archives, it’s also the archive of the skills of the workers. And those need to be saved.

‘It’s a bit like the ravens in the Tower. Stoke needs its potteries,’ Moore continued.

Certainly, the phrase ‘Made In England’ still counts.

7. A regal mould from a commemorative set of ceramics 8. & 9. It takes staff seven years to acquire essential skills. This is the last place in the world where prints are still transferred by hand

7. A regal mould from a commemorative set of ceramics 8. & 9. It takes staff seven years to acquire essential skills. This is the last place in the world where prints are still transferred by hand‘There’s a terrible issue in the industry,’ he added. ‘I won’t name the very famous brands, but they mark their wares “England” when they’re actually made in Jakarta. If you want to buy British pottery, look for the words “Made in England”.’

The regenerated pottery, which also attracted funding from English Heritage, the Regional Growth Fund, the Heritage Lottery Fund and a host of private donors, now has a visitor centre, a cafe, a shop and even a wonderful ceramic sculpture of the pottery by the artist Philip Hardaker.

Indeed, it is hoped that the site will attract 30,000 visitors a year. But as Prince Charles toured, it became clear that this is first and foremost a place of manufacture, of creation, of graft and skill and good, old-fashioned elbow grease.

The woodwork is worn and creaky; the paths are cobbled. Spend a moment in the working parts of the pottery and you will find yourself coated in a fine layer of dust and cobweb. It’s the real thing.

10. Prince Charles arrives at the Middleport Pottery on a canal boat 11. A Felicity tissue design is carefully applied to a teapot 12. Middleport factory viewed from the canal – traditional transport for all its wares 13. The plentifully staffed tissueprinting room in the 1930s

10. Prince Charles arrives at the Middleport Pottery on a canal boat 11. A Felicity tissue design is carefully applied to a teapot 12. Middleport factory viewed from the canal – traditional transport for all its wares 13. The plentifully staffed tissueprinting room in the 1930sAs Ros Kerslake, chief executive of The Prince’s Regeneration Trust, said, the project has brought Middleport up to ‘21st-century standards but kept the huge uniqueness of how it was in 1888… we tried to be sensitive, to not over-restore or over-modernise the place.’

Lily Wakefield, 79, was one of many who came to see Prince Charles on the day of his visit. Vivacious, with a sparkling sense of humour, she was born on one of the barges that served the potteries here. ‘There were no televisions,’ she told me, ‘so we used to play in the clay sheds.

‘When I was old enough, my parents would give me little jobs, like steering the boat. They would put me on a stool and you daren’t bang the boat, or as we’d say “stem it up”.

‘I did do that once, during the war, when I was about eight. My mother wanted me to steer it one day and I didn’t want to because there was this one turn I didn’t like. “I shall stem it up,” I said, but she told me to do it – and I did [stem it up]. Twenty-two tonnes of soda ash.’

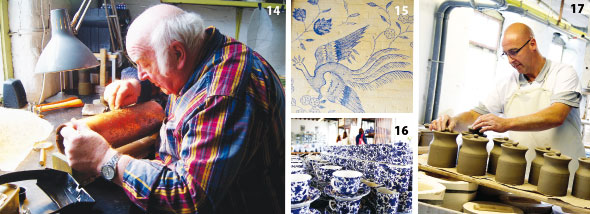

14. Tissue is delicately applied to the biscuit ware (first firing of pot) 15. & 16. A bird theme prevails in the Blue Asiatic Pheasant (top) and Blue Regal Peacock ranges 17. Pots are produced by casting or pressing the clay, then assessed before firing

14. Tissue is delicately applied to the biscuit ware (first firing of pot) 15. & 16. A bird theme prevails in the Blue Asiatic Pheasant (top) and Blue Regal Peacock ranges 17. Pots are produced by casting or pressing the clay, then assessed before firingThis area is filled with stories like that – and the potteries often play a starring role. It’s part of what makes Middleport such an enchanting place.

In his speech, Prince Charles said: ‘As some of you have no doubt heard me say before, to your intense boredom, I suspect, I have always believed that heritage-led regeneration – in other words, finding new uses for redundant heritage buildings and turning them into real assets for the local communities – is absolutely vital in bringing new industry and business to the area, boosting the economy and providing much-needed employment and prosperity.’

Indeed, while there are no doubt many obstacles still ahead for Britain’s last Victorian pottery, for now at least, Middleport is living proof that heritage is something we should avoid ‘stemming up’. Like Middleport’s Burleigh ware, it’s just too precious.

Middleport Pottery, Port Street, Burslem, Stoke-on-Trent: 01773-740740, www.burleigh.co.uk

Murals (photographed) painted by Joyce Iwaszko

For more information on The Prince’s Regeneration Trust: www.princes-regeneration.org