Young at heart..

With Rosen’s catchy verses and Helen Oxenbury’s engaging illustrations, the story is familiar to most parents and has a timeless appeal: a group sets off on a quest, overcoming increasingly daunting obstacles along the way, with the defiant refrain: ‘We’re not scared!’

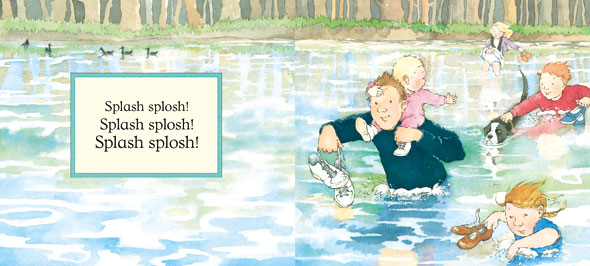

Rosen took an old folk rhyme and put his signature stamp to it, complete with sounds of squelching mud, swooshing snowdrifts and echoing footsteps. With a poet’s ear for rhythm, he turned it into a chant that carries the rapt reader along.

But how do you go from a campfire song to an international bestseller, translated into 18 languages? ‘Very simple: hand it to Helen Oxenbury,’ he says, with disarming modesty. ‘The trick is, you happen to know a rhyme, and someone clever in a publishing house, like David Lloyd [at Walker Books], thought I would be good to write down the words. Then he chose Helen and the designer, Amelia Edwards: they made the book. In picture books, the people who write the words just provide a kind of platform.’ But Helen disagrees: ‘You’re so wrong! It’s the idea that inspires the illustrator!’

This exchange sets the tone for the rest of our conversation: each crediting the other for the book’s success. But it is clear that their collaboration, like Gilbert and Sullivan’s, has been a creative alchemy: the whole greater than the sum of its accomplished parts. They bicker amicably and finish each other’s sentences but, as it turns out, they only met after the book was finished – which makes their like-mindedness uncanny.

‘Michael just left me to it,’ says Helen, who trained at the Central School of Art and Design and worked in film and TV before turning to book illustration. Given creative carte blanche, Helen faced the luxury and challenge of a relatively blank canvas: ‘When I got the text I thought, this makes a wonderful story, it’s got all the ingredients. But the characters and the landscapes weren’t explained. That makes it so wonderful for an illustrator, you can contribute so much. So I tried a few ideas, but then I thought: let’s bring it down to a family going on an adventure.’ Perhaps this accounts for the book’s enduring appeal: an ordinary family facing extraordinary dangers.

She has peopled Michael’s ‘platform’ with an expressive cast: a boy, two girls, a baby and an adult male, plus a dog, based on her own. And, of course, that bear. Michael points to an image of the huge brown beast, peering menacingly through a windowpane: ‘Scariest picture in the book. You know what that reminds me of? Helen must have known, intuitively: one of the most important pictures of my whole childhood was Simpkin in the Tailor of Gloucester, looking at the mice through the glass in the door. It takes me right back to being four years old – and terrified.’ ‘Children love being terrified,’ Helen chips in, ‘as long as it’s all right in the end.’ On the final page, the family and their dog are safely tucked up in bed.

‘The dog is important in children’s books,’ Michael continues, ‘because a child can identify with another child, but he can also be that dog. He is definitely one of the gang.’ It is this finely tuned empathy with the wonder, thought patterns and anxieties of childhood that makes Rosen’s work so popular. How has he managed to retain an imaginative toehold in childhood? ‘I’ve continuously had children under the age of 15, over a period of 38 years, so I am the longestrunning school-parent in existence!’

As a childless adult with no young relatives, I didn’t expect to be so moved by a book aimed at small children. Again, Michael puts it all down to the pictures: ‘It doesn’t surprise me. Helen is a brilliant life-drawer, so you can always see the shape of the bodies inside the clothes. The emotion is in their bodies.’

Rosen does not spare his young readers the rougher edges of human experience – mud, predators, and worse. While much contemporary children’s fiction can be rather sanitised, I suggest, he has bravely tackled difficult themes: The Sad Book is based on the death of one of his sons. ‘It came about because I’d already written about that character, Eddie the boy, and children would ask, “what happened to Eddie?” So I had to say, well, he died. At the time it didn’t feel brave so much as necessary.’

And yet there is also an unabashed playfulness in his work. ‘A book is a nice place to go, to be entertained, like when you have a birthday party. Books are mini birthday parties. This one,’ he says of the Bear Hunt, ‘is a romp.’

‘A romp’, in fact, is how he might describe reading: something to be enjoyed for its own sake. He is a vocal opponent of the current system for teaching children to read in schools, with its exclusive use of phonics and emphasis on test results. Used in isolation, ‘systematic, synthetic phonics’ (he spits out the words with dislike) turns reading into mere ‘decoding’, leaving no room for meaning, feeling or fun.

‘You need multiple methods, one of which is having a rollicking good time when you open this wonderful carboardy paper object. You may look at these squiggles and go, this is the river, and you see the word river and make sense of it that way. If you do that at the same time as you do the phonics, it all works together. But what I am saying is heresy for the present regime.’ He is an eloquent thorn in the side of the educational establishment, having recently published an alternative curriculum.

With his warmth, originality and rebellious streak, Michael Rosen would make the most inspiring school teacher – with Helen’s drawings as a teaching aid, of course. ‘When I go into schools, I show them the incredible magic we create by putting figures on a page.’ His magic cannot be quantified by government metrics, but the world would be a much duller place without it.