By Roderick Conway Morris

The bean-counters of ancient Mesopotamia are credited with inventing writing for accounting and administrative purposes in around 3,300 BC. Some 300 years later, the Sumerians were the first to use these systems to represent their language in writing.

One of the first uses they put this to was to inscribe names and prayers on grave goods. This was related to their belief that a person would live on beyond death if their name was spoken – we can all still get a sense of this when reading the names on gravestones, or a letter from someone no longer alive.

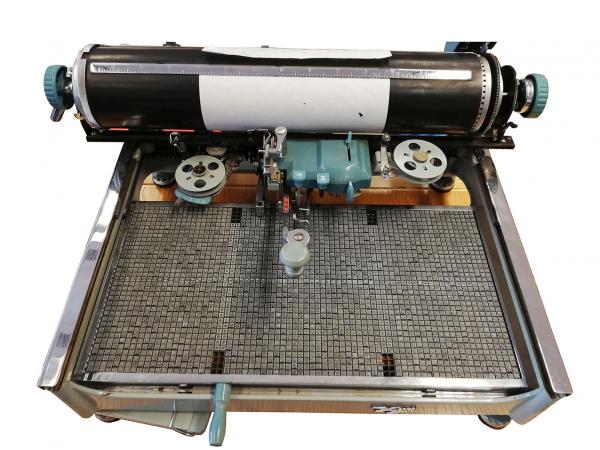

Indeed, the extraordinary sense of continuity across time the invention of writing has given to the human race is one of the most powerful themes underlying the British Library’s absorbing exhibition, Writing: Making your Mark. It traces the story of writing over 5,000 years through some 100 objects, representing more than 40 writing systems, written on a plethora of surfaces, from stone and papyrus to palm leaves and paper. Exhibits include an enormous Mayan carved slab, a Chinese typewriter with an alarming 2,418 characters, Alfred Lord Tennyson’s worn-out quill pen and an enraged four-page telegram from the playwright John Osborne to an unappreciative theatre critic.

Chinese Typewriter

About two-thirds of the globe use some form of alphabetic system, the shortest, used in Papua New Guinea, with a mere 12 letters; the longest, in Cambodia, with 74. All of these ultimately derive from alphabets in the ancient south-eastern Mediterranean, where the Phoenicians used theirs for trade, while the Greeks developed the Phoenician alphabet to record Homer’s epics. The Chinese and Japanese use systems of characters, which may contain both symbolic and phonetic elements, while the Japanese also weave into texts two additional syllabic alphabets, hiragana and katakana, making theirs possibly the most complex writing system in the world.

Our capital letters have barely changed since ancient Rome and our lower-case letters remain little altered from Charlemagne’s time 1,200 years ago. Italic script was developed by the printer Aldus Manutius in Venice in around 1500. This made it possible to print clearly on a much smaller page, giving rise to the ‘pocket book’, the format of paperbacks today. In Portland, Oregon, Steve Jobs’ inspirational teacher Lloyd Reynolds, an expert on historic typefaces, was decisive in Jobs’ later insistence on attractive lettering on Apple’s screens.

The father of 20th-century calligraphy was Edward Johnston, who was inspired above all by the British Library’s 10th-century Ramsey Psalter. He went on to design his lettering for the London Underground in 1916 that is still in use, and one of the most popular fonts worldwide.

- Until 27 August at the British Library, London; 0330-333 1144, www.bl.uk